Activist Constellations: Recovering Black Women's Labor and Leadership

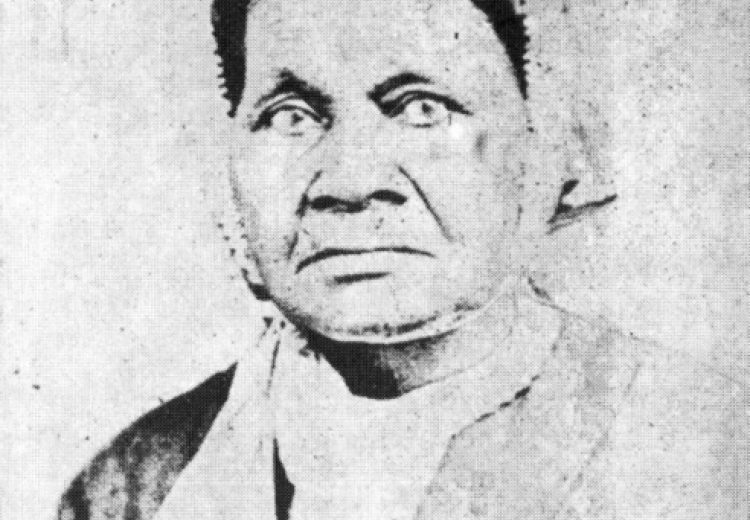

Priscilla "Mother" Baltimore is remembered as a founder of Brooklyn, Illinois, one of the oldest towns incorporated by Black Americans.

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

The Colored Conventions Movement was a series of political conventions held across the country during the nineteenth century. Gathering in local, state, regional, and national conventions, free and formerly enslaved Black people called for emancipation and delivered demands for voting rights and educational equality. In recent decades, the Colored Conventions Project (CCP) has brought renewed attention to the movement. The project’s efforts to preserve, digitize, teach, and interpret the convention movement have reconfigured the literature on emancipation and Reconstruction. By centering Black political actors and networks of activism, scholars of the convention movement have lengthened the chronology of Black freedom struggles, challenged the regional frames through which slavery has been interpreted, and revealed a rich world of political organizing beyond the white abolitionist leaders who are often treated as archetypes of Civil War-era activism. To learn more about the convention movement and the CCP, including ways to teach with project resources, see the Rethinking Reconstruction: Black Community and Political Organizing teacher's guide.

However, as CCP organizers have emphasized, centering the Colored Conventions is not a sufficient strategy for recovering the richer history of Black political organizing in the nineteenth century. Conventions were composed of Black men, and the records they produced and circulated mirror this reality. These documents primarily recount male delegates’ deliberations and demands for political equality. Women are largely absent from these records, both as attendees and as individuals with political rights and agency more broadly. If our examination of the convention movement engaged these proceedings alone, we would overlook a significant number of the people who steered the movement.

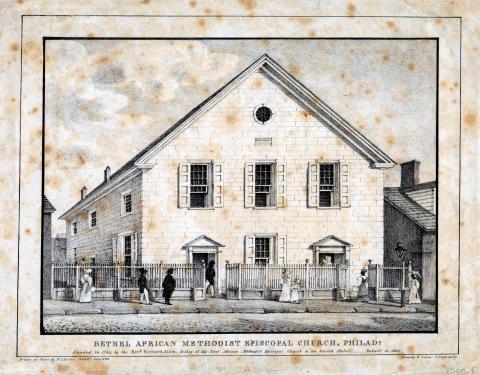

Recognizing that the convention movement relied upon women’s ideological and material labor, the CCP has made it their ethical imperative to center Black women. The collective’s research demonstrates how recovering women’s labor and leadership enables us to access a larger world of Black activism in the nineteenth century. By researching the women who belonged to churches where conventions were held, who waged campaigns for desegregation and suffrage, who accompanied male delegates to conventions, and who operated boardinghouses and restaurants, we can uncover the ideas and institutions that propelled the convention movement forward.

Assembling the Constellations of Black Women’s Activism

We can begin to recover women’s roles with a simple question:

Where did conventions begin and end?

This question asks us to consider the labor that shaped the material conditions and political agendas of conventions. It suggests that conventions were not bound by the time and place at which delegates gathered. We can instead think of these physical gatherings as starting points for tracing the larger constellation of people, ideas, and processes that made up the movement. Assembling this constellation enables us not only to correct the erasures that enshroud historical realities but to get closer to the everyday action of history and the processes through which political change is produced.

A constellation is defined as a group of stars that form a pattern. It is a useful concept for interpreting Black women’s activism because it represents an interconnected network through which we might trace relationships between people, ideas, and places. Constellations also offer an apt metaphor for Black women’s roles in the movement because they are oftentimes visible to people on Earth only in fragments. The patterns we can see on any given night depend on the time, latitude, season, and a plethora of other observational conditions. Additionally, the stars that make up constellations are constantly in flux, changing the shape of the entire pattern over the course of several hundred years. Similarly, the "observational conditions"—primary sources and research questions—through which we access the history of the convention movement shape what we can see. By experimenting with these conditions and becoming persistent observers of the past, we might uncover a more precise history of nineteenth-century activism.

Recognizing Political Agency in Domestic and Caring Work

The CCP’s What did they eat? Where did they stay? Black Boardinghouses and the Colored Conventions Movement models this process of persistent inquiry. Focusing on four conventions—the 1859 New England Colored Citizens Convention, the 1865 Convention of the Colored People of New England, the 1848 National Colored Convention in Cleveland, OH, and the 1865 First Annual Meeting of the National Civil Rights League in Cleveland, OH—this exhibit considers the political activity that took place beyond the convention hall. Through maps and other data visualizations, interpretations of newspaper advertisements, and biographies, the exhibit demonstrates how the boardinghouses where delegates stayed and the food they ate shaped the ethos of the movement.

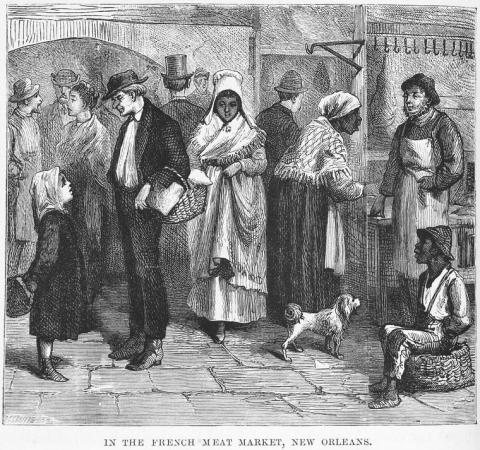

The exhibit shows how Black women used domestic and caring work to express agency and gain access to political discourse. It constructs a constellation by putting places like convention halls into orbit with boardinghouses and eateries, and primary sources like convention proceedings into orbit with menu and boardinghouse advertisements. In other words, the exhibit shifts the observational conditions through which we interpret conventions. By drawing these connections, the exhibit demonstrates how the movement was defined by connected and continuous hubs of political activity rather than isolated convention gatherings across the country.

Considering the Relationship Between Past and Present

The constellation metaphor for Black women’s activism is also useful because it provides a more nuanced framework for exploring personal and structural relationships between the past and present. Like constellations, there are more components and factors at play in any historical moment than we might recognize from our standpoints in the present. Our witnessing of constellations is not what makes constellations real. The existence of constellations is not premised upon our acknowledgement. However, if we wish to make meaning and draw significance from such phenomena, we must do more than observe. Similarly, our recognition of Black women’s contributions to the convention movement is not the act that affirms their contributions. If we are to understand the bearing of convention history on our present moment, we must do more than witness and name women’s material and ideological labors. Our task is to untangle and disrupt the historical and historiographical processes that reproduce the erasure of women’s history from convention history.

Equipping students to consider the relationship between our contemporary perspective and our view of the past can engender more creative and agentic approaches to historical inquiry. The CCP’s Black Women’s Economic Power: Visualizing Domestic Spaces in the 1830s exhibit illustrates the questions we can ask and the places we might look in order to identify and repair the gaps between our perceptions of history and the historical realities of the convention movement. Focusing on five conventions held in the same neighborhood of Philadelphia between 1830-1835, this exhibit explores the economic power Black women exercised as dressmakers, bakers, and boardinghouse keepers.

The exhibit pairs biographies of women like milliner Grace Bustill Douglass and confectioner Sarah Curtis with interactive maps and other visualizations to show how Black women originated, practiced, and revised the principles of Black economic mobility and collective uplift that defined the movement. Going far beyond narrating the lives of individual women, the exhibit models strategies for building a stereoscopic view of history out of a flattened narrative. The exhibit uses the limited sources and knowledge we have of women’s contributions to refocus our attention, generate new lines of inquiry, and tell a story of convention activism that extends beyond the convention hall and Philadelphia and between generations of activism. By attending to the layers of the past in this way, we might support students in developing an operative sense of historical consciousness. Learning how to correct the exclusion and omission of women from historical narratives can equip students with the analytical and ethical wherewithal necessary to confront contemporary social injustice.