Afro Atlantic Art: Everyday Lives

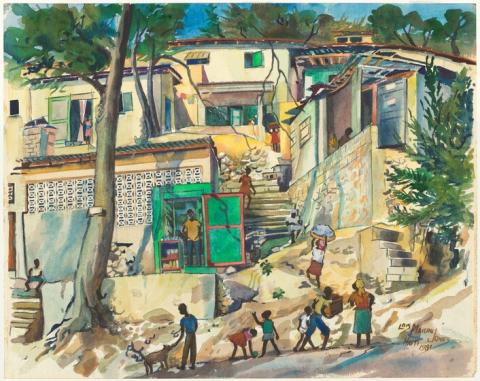

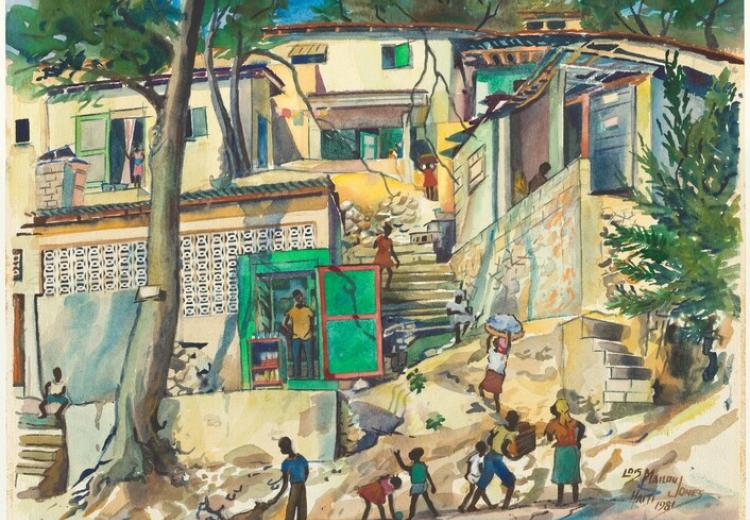

Lois Mailou Jones, The Green Door, 1981

Courtesy National Gallery of Art

This resource, provided courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, presents a variety of artworks, from the 17th century to the present, that highlight the presence and experiences of Black communities across the Atlantic world (the relationships between people of the Americas, Africa, and Europe). Use the pieces in this collection to engage your students in conversation about the celebrations and struggles in the daily lives of Black people.

Find related artwork and activities in the EDSITEment Teacher's Guide Arts of the Afro Atlantic Diaspora.

Horace Pippin, School Studies, 1944

Horace Pippin, School Studies, 1944, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1991.42.1

Horace Pippin turned to art after serving in World War I in the African American regiment known as the Harlem Hellfighters. After Pippin was shot by a sniper and lost full use of his right arm, he received an honorable discharge from the military. Pippin returned to his hometown of West Chester, Pennsylvania, and taught himself to paint using his left arm to support his injured right arm.

This painting may be inspired by memories of Pippin’s childhood, depicting members of an African American family pursuing a variety of activities in a single, multipurpose room with common household items such as rag rugs, quilts, a stove, and an alarm clock. This artwork gives a glimpse into the realities of everyday life for Black families in the northern United States at the turn of the 20th century.

- What feeling does this scene give you?

- Imagine this artwork represents the beginning of a story—what might happen next?

- Read Pippin’s account of his own life. What interests or surprises you about the course of his life and career?

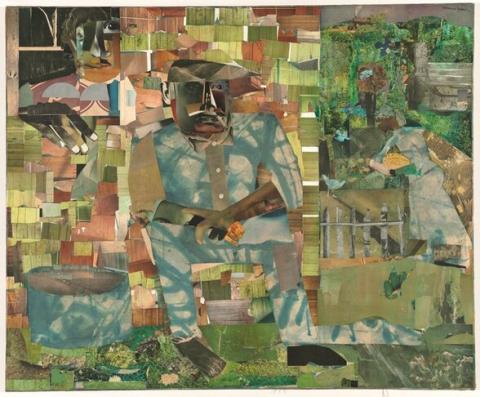

Romare Bearden, Tomorrow I May Be Far Away, 1967

Romare Bearden, Tomorrow I May Be Far Away, 1967, collage of various papers with charcoal, graphite, and paint on paper mounted to canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Paul Mellon Fund, 2001.72.1. © Romare Bearden Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Romare Bearden was one of more than 6 million African Americans who fled the US South between 1916 and 1970 during the Great Migration. His family left North Carolina for Harlem, New York City, where Bearden grew up surrounded by poets, writers, and musicians. He worked as a social worker for several decades, during which time he spent nights and weekends on his art, creating collages using images from photo-magazines such as Life and Ebony.

Bearden was often inspired by music; the title of this collage is a reference to a lyric from “Good Chib Blues,” a song popularized by blues singer Edith North Johnson. The collage is rich with details suggesting memories of rural life in North Carolina: grass, a wooden fence, a watermelon. In the top right corner is an image of a train, possibly alluding to the journey of the Great Migration.

- What details stand out to you in this artwork?

- What visual elements would you consider important to include in an artwork centered around your own family memories?

Lois Mailou Jones, The Green Door, 1981

Lois Mailou Jones, The Green Door, 1981, watercolor over graphite on wove paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, William A. Clark Fund), 2015.19.2951

In The Green Door, Lois Mailou Jones presents a scene of everyday life in the Caribbean nation of Haiti. Mailou Jones was married to Haitian artist Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Noel, and the two visited the island often. In this vibrant scene, Mailou Jones has taken care to show adults and children at work and at play, living in a dense community of brightly colored stacked houses.

Influenced by the Harlem Renaissance of her youth, Mailou Jones cultivated a lifelong interest in African and African Diasporic cultures and artistic traditions. In the 1960’s, she traveled to eleven African countries to meet, learn from, and document the work of contemporary artists. Through her teaching at Howard University for more than forty years, Mailou Jones raised awareness of the contemporary artistic traditions developing in Black communities across the globe for a generation of Black artists in the United States.

- What details stand out to you in this painting?

- How does the artist give a sense of place and identity to Haiti?

- How do these characteristics compare to the place where you live?

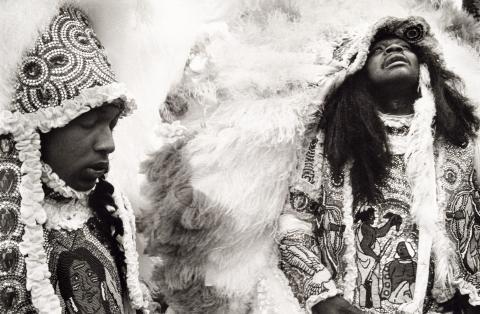

Marilyn Nance, The White Eagles, Black Indians of New Orleans, 1980

Marilyn Nance, The White Eagles, Black Indians of New Orleans, 1980, gelatin silver print, Collection of Light Work, Syracuse

Much of artist Marilyn Nance’s work focuses on the spiritual traditions of different Black communities in the United States. In this photograph she captures Black Indians in New Orleans wearing ceremonial dress. It is popularly believed that Black Indians are descendants of Native Americans and Black Creoles, and by the 19th century, Black Indians had formed their own tribes with specific traditions, including songs and dances performed during Mardi Gras. Here, they wear the headdresses of White Eagles, the oldest Black Indian tribe in New Orleans’ history. The Black Indians’ traditions are an example of religious syncretism, the blending of multiple religious beliefs and rituals into a new system—common in communities of the African Diaspora.

- Where can you see cultural blending in your own communities?

- Watch a video of the White Eagles celebrating Mardi Gras and compare Nance’s photograph to the celebration.

This resource is drawn from the content of the Afro-Atlantic Histories exhibition organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Museu de Arte de São Paulo in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, Washington. All related materials found on EDSITEment have been provided courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.