Using Chronicling America to Tell a Fuller Story: How Historical Newspapers Represent Different Perspectives

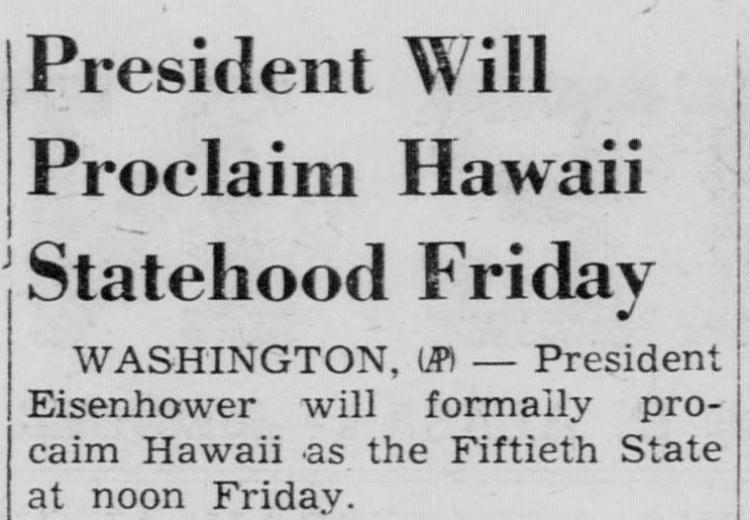

The Nome Nugget, an Alaskan newspaper, announced in the August 19, 1959, issue that Hawai‘i would be proclaimed the fiftieth state.

Historical newspapers offer access to the past and allow researchers to trace the development of ideas and events. Newspapers can reveal not only turning points in history and the speed of those turns but also the debates and perspectives held by people in that historical moment. Newspapers may represent a national view or be highly localized, offering a glimpse into the opinions held in individual communities. As rich and layered resources, historical newspapers can play an important role in research for a National History Day® (NHD) project.

Created through a partnership between the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the Library of Congress, Chronicling America offers users the ability to search and view more than 20 million digitized newspaper pages from 1777 to 1963 and to find information about American newspapers using the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP). Currently, Chronicling America includes newspapers in 22 languages in addition to English and has contributions from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. With this temporal, linguistic, and geographic reach, Chronicling America encompasses a range of subject matters that is critical to U.S. history.

The Red Summer: A Time of Turmoil and Transformation

In 1919, racial hostility triggered violent attacks on African Americans in more than 20 cities and towns across the United States, damaging or destroying many Black communities and resulting in the deaths of hundreds of people. Writer and civil rights leader James Weldon Johnson called this wave of violence the Red Summer. Though 1919 clearly represented a low point for racial justice in the United States, this year of bloodshed can also be seen as a turning point, as it was followed by decades of organized activism that, in many ways, laid the groundwork for the civil rights victories of the mid-twentieth century.

Red Summer came at a time of tremendous social change in the United States. African Americans had recently begun leaving southern, more rural states in large numbers, seeking better opportunities away from the restrictions of Jim Crow segregation. This Great Migration, which continued for several decades, fueled a surge of growth in northern and eastern cities and spurred the expansion of existing Black neighborhoods and institutions as well as the creation of new ones.

At the same time, millions of military personnel were returning home from World War I. These included more than 350,000 African Americans who served in the armed forces, where they faced routine discrimination and were restricted to segregated units. Author and civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois said of these service members, many of whom had been deployed in Europe and fought under trying conditions, “Those men will never be the same again. You need not ask them not to go back to what they were before. They cannot, for they are not the same men any more.”1 This turning point in expectations was met with violence.

The violence of Red Summer began in the spring and built throughout the year in rural Georgia; the District of Columbia; Chicago, Illinois; Knoxville, Tennessee; Omaha, Nebraska; and many other cities and towns. Dozens of people died in lynchings, indiscriminate shootings, and the burning of African American homes, churches, and, in some cases, entire neighborhoods. On August 28, 1919, the editorial page of Madison’s The Wisconsin Weekly Blade remarked, “We arise to inquire if the world has yet been made safe for democracy.”2

Some of the bloodiest days of the year came in late September in what became known as the Elaine Massacre.3 Late on the night of September 30, 1919, African American sharecroppers attended a union meeting in a church outside of Elaine, Arkansas. White law enforcement officers arrived in a car, and shots were exchanged. It is unclear who fired the first shot. A railroad security officer was killed, and a deputy sheriff was injured.

Soon after, hundreds of armed white people from neighboring counties flooded the area, some drawn by rumors of an African American insurrection. In the following days, dozens to hundreds—no reliable count was ever made—of African Americans were killed in and around Elaine.

The NAACP, which had been founded just over a decade before to advance the rights of African Americans, played an active and visible role in investigating and combating the injustices of the Elaine Massacre, as well as other atrocities in 1919. The years before and after the Red Summer saw a period of tremendous growth for the NAACP. These legal challenges and investigations presaged the role the NAACP would play in the civil rights battles of the coming decades.

Discovering Multiple Perspectives Using Chronicling America

The events of Red Summer were reported and debated in newspapers as they happened. More than a century later, those newspapers provide students working on NHD projects with the opportunity to explore these turning points in history in depth. By analyzing historical newspaper reports of tumultuous and contentious episodes, students can understand the immediate and often chaotic nature of emerging news reports and see how different newspapers provided different accounts of the same events. A link to an “About” page appears directly under every newspaper entry in Chronicling America. Examining that page provides students with valuable information about its owner, editors, and audiences, fueling their inferences about that newspaper’s points of view.

Searches in Chronicling America reveal that, soon after violence broke out in Elaine, newspapers made claims about its causes. On October 3, 1919, The North Mississippi Herald, published about 100 miles from Elaine, advanced its version of the story: “1500 Armed Negroes Prepared to Battle, while Federal Troops with Machine Guns Are Rushed to Scene of Disturbance. Clash Precipitated When Deputy Sheriffs Attempted to Arrest a Notorious Negro Bootlegger—Negroes Fired Upon the Officers Without Warning, Then Whole Negro Section Took Up Fight.”4

A different perspective appeared in a Kansas newspaper. The October 2, 1919, issue of The Topeka State Journal saw shadowy organizations behind the bloodshed and declared that “NEGROES ARE BEING INCITED,” “Organized Propaganda To Stir Them Up, Charge,” and “‘We’ll Battle for Our Race Till End, One Says.’”5 On October 6, 1919, The Prescott Daily News in Arkansas ran a story headlined “GHASTLY PLOT BY BLACKS REVEALED,” claiming that a secretive organization planned to “shoot down all whites in sight” and that its members had been gathering at the church outside Elaine when the sheriff and a railroad security officer were ambushed there.6

The Chicago Whip, whose front page bore the motto, “Make America and ‘Democracy’ Safe for the Negro,” disputed that claim on October 8, 1919. “It is said that many white radicals had given the colored people inflammatory literature and urged them to rise against all whites. This report is confounded and the literature was merely an appeal to the colored people to protest to white leaders against further cruelty, injustice and lynching.”7 The Monitor in Omaha, Nebraska, conducted its own investigation and, on October 30, 1919, ran a headline declaring, “Associated Press, as Usual, Withholds Significant Facts—Vicious Whites Under Pretense of ‘Suppressing Negro Uprising’ Mob and Kill Scores of Negroes and Imprison Hundreds of Others.” A lengthy article included sections titled “Summary of Half Truth Circulated by Press” and “The Motive Behind the Hullabaloo.”8

Students can also use historical newspaper pages from Chronicling America to examine the other stories covered alongside the attacks of Red Summer, both to gain a sense of the events of the times and to examine the priorities of a newspaper’s decision-making staff. In several newspapers in 1919, Red Summer violence shared front-page space with the aftermath of World War I and the illness of President Woodrow Wilson. In many issues of Omaha’s The Monitor, stories about the Elaine Massacre were sidelined by coverage of a horrific lynching in Omaha and the burning of the city’s county courthouse. In Virginia, the Richmond Times-Dispatch ran a stacked headline in which the horrors in Arkansas were followed by another leading story of the day: “NINE PEOPLE ARE KILLED IN ARKANSAS RACE RIOTING” and “CINCINNATI DEFEATS CHICAGO IN FIRST GAME, 9 TO 1.”9

Hawaiian Annexation and Statehood

Hawai‘i’s journey from kingdom to U.S. territory to fiftieth state represents a turning point in the history of the Hawaiian Islands, the United States, and the central Pacific Ocean region. Each step on that journey was subject to many public perspectives.

Although the official name recorded on the 1959 Statehood Act identifies the name of the state as “Hawaii,” we have elected to use the ‘okina, the mark that resembles an upside-down apostrophe between the i’s in Hawai‘i, for consistency. The word Hawaiian does not have an ‘okina. For more information on the written Hawaiian language, visit iolanipalace.org/information/hawaiian-language/.

The Hawaiian Kingdom was founded in 1795 when Kamehameha the Great of Hawai‘i conquered and unified the islands of O‘ahu, Maui, Moloka‘i, and Lana‘i under his government. By 1810, the entire archipelago had been brought under the control of the Kamehameha Dynasty. At the same time, the island nation was gaining more and more international interest. British explorer James Cook was the first Westerner to encounter the Polynesian islanders on January 18, 1778. American and European traders quickly followed.

Great Britain, the United States, Japan, and other globalizing nations began to take an interest in Hawai‘i’s natural exports, especially sugar. The islands' location in the Pacific was also strategically valuable for traders and navies as a resupply port. White Christian missionaries from the United States traveled to the islands seeking to convert the native populations, and in 1848 a land distribution act allowed non-Hawaiians to purchase land for the first time. By the 1850s, petitions for the United States to annex Hawai‘i came from these missionaries, plantation owners, and even some native Hawaiians who joined together to establish the Reform Party. On January 17, 1893, the Committee of Safety, a pro-annexation group of American citizens and Hawaiian citizens of American descent, led a coup to overthrow Queen Liliʻuokalani and established the Republic of Hawai‘i.

Their goal of annexation did not come to fruition until nearly the close of the century, when William McKinley succeeded Grover Cleveland as president, bringing a renewed executive focus on Hawai‘i into the White House. As the Spanish American War began, President McKinley and others around the country saw Hawai‘i as a necessary base from which the United States could project its power into the Pacific, specifically against Spanish colonial holdings in the Philippines. In August 1898, President McKinley agreed to Hawaiian attorney Sanford Dole’s request for annexation, and Hawai‘i was officially incorporated as a territory of the United States with the passage of the Newlands Resolution.10

Although most landowners benefited economically from Hawai‘i’s new territorial status, many native Hawaiians and non-white residents wanted Congressional representation and all the rights enjoyed by residents of the 48 states. Almost immediately following annexation, many Hawaiians began working toward attaining statehood. The first official petition for statehood was filed on August 15, 1903, just five years after annexation. This petition was denied, along with several other requests over the next five decades. During this time, Hawai‘i’s governors and judges were all federally appointed, and the territory’s one congressional delegate was a non-voting representative. This lack of local self-determination helped wealthy white plantation owners remain in power.

After the conclusion of World War II, efforts were redoubled by both Hawaiian and white citizens of the territory. Statehood would mean an end to taxation without representation, popularly elected state officials, and the guaranteed protection of rights that other U.S. citizens enjoyed. Many mainland politicians also recognized the strategic value of having an American presence in the Pacific and began to agitate for statehood as a result. In March 1959, Congress passed a bill admitting Hawai‘i as the fiftieth state. A citizen’s referendum held in Hawai‘i in June confirmed that the majority of people living in the territory accepted it. Finally, on August 21, 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the bill into law. Almost 60 years after annexation, Hawai‘i was finally one of the United States.

Discovering Multiple Perspectives Using Chronicling America

Many political factors influenced American sentiment regarding statehood for Hawai‘i. In part, racial tensions kept many Americans from supporting full statehood for the island territory. Asian immigrants and their children made up a large portion of the Hawaiian population. Anti-Asian sentiment led many to believe that if Hawai‘i was granted full citizenship rights and protections, they would betray American values and principles. These racist views grew with the entry of the United States into World War II following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Many of these debates can be traced through the historical newspapers found in Chronicling America.

These newspaper articles highlight the diversity of perspectives the national media had about events occurring in Hawai‘i. In many places in the continental United States, the conversation centered around how adding new territory to the union would affect domestic and foreign politics. The February 5, 1898, issue of The Oasis from Nogales, Arizona, had a brief article recognizing the patriotism the Illinois House of Representatives displayed by voting to annex Hawai‘i.11 This perspective, written for an audience living in a territory (Arizona became a state in 1912), puts the conversation in the context of what adding new territory will mean for the United States. Another article from the July 12, 1887, issue of the Daily Independent in Elko, Nevada, states this perspective even more succinctly, saying “[United States Naval vessels] are fully able to protect the interests of the United States.”12

Local Hawaiian newspapers’ coverage of annexation had an understandably different focus. Honolulu’s The Independent September 13, 1897, issue includes two articles covering the coup and attempts to annex Hawai‘i, both of which decry the actions of the provisional government under Sanford Dole and showcase their anti-annexation sentiment.13 These articles illustrate how, to people living in the Hawaiian Islands, these issues were critical and raised questions about national sovereignty, self-determination, and the immediate consequences of these events. It is important to remember that even when reading these articles from Hawaiian newspapers, questions about whose perspective we are seeing must be asked. Fortunately, reports on the activities of groups such as the Women's Hawaiian Patriotic League show the actions being taken by people whose perspectives may not be fully present in other written primary sources.

Following World War II, agitation for statehood began once again. During the war, Hawai‘i was extremely important for Allied efforts in the Pacific, and many leaders felt that Hawaiian statehood would benefit national security. At that time, Hawai‘i was controlled by Republican politicians, which led many Republicans both on the islands and in the continental United States to advocate for its admission into the Union. In 1947, the first of several bills on the issue was debated by the U.S. House of Representatives before dying in the Senate. Democratic leaders feared that if Hawai‘i was admitted as a full state, its Senate seats and electoral powers would give greater control to Republicans. Republicans, however, feared the same about potential Alaskan statehood. As a result, multiple bills were brought forward by both parties before being dropped in Senate committee meetings or voted down. These partisan debates were covered extensively in the Evening Star, a Washington, D.C., newspaper whose readers faced their own struggles with political self-determination. A March 6, 1950, article expressed anxiety about an upcoming House vote, referencing promises made to the people of Hawai‘i.14 On May 20, 1954, the paper lamented another failed campaign with the headline “Alaskan-Hawaiian Statehood Appears Doomed This Year.”15

Finally, a package deal for both Alaska and Hawai‘i came under consideration. Both political parties felt that it would be politically advantageous to add a territory they believed they could count on, but it took until the end of the decade for joint statehood to become a popular platform. In 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower voiced his support for both territories to become states. The following January, Alaska became the forty-ninth state and paved the way for Hawai‘i’s Congressional approval in March of the same year. This was soon followed by a June referendum in Hawai‘i, with a vote of 132,773 to 7,971 in favor of statehood. The Alaskan newspaper, The Nome Nugget, announced to its readership, who had only recently marked that same achievement, that finally, Hawai‘i would be proclaimed the fiftieth state to join the Union.16

Conclusion

Turning points in history are very much a matter of perspective. Events that seem transformational to those living through them might seem less so to people viewing them from a different time or place. Historical newspapers allow researchers today to immerse themselves in a particular historical moment, making it possible to identify turning points that a more remote point of view might not allow. In addition, these newspapers enable researchers to discover how those turning points were perceived and discussed at the time. This adds richness and complexity to our understanding of even well-known transformational events, thereby increasing students’ awareness of the need to consider varied sources and perspectives, benefiting their work as historians and their role as citizens.

-

“Prof. W. E. B. Du Bois Addressed a Vast Crowd . . .,” The Broad Ax [Salt Lake City, Utah], May 24, 1919. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024055/1919-05-24/ed-1/seq-4/.

-

“If We Must Die,” The Wisconsin Weekly Blade [Madison, Wisconsin], August 28, 1919. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025842/1919-08-28/ed-1/seq-4/.

-

Although the violence in and around Elaine is currently known as the Elaine Massacre, at the time it was generally described using different terms, including “race riot.” Teachers should support their students in exploring the different language used to describe these violent events and in examining the implications of each term.

-

“Pitched Battle Whites-Negroes in Arkansas,” The North Mississippi Herald [Water Valley, Mississippi], October 3, 1919. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87065497/1919-10-03/ed-1/seq-1/.

-

“Governor Shot At: 10 Die in Race War,” The Topeka State Journal [Topeka, Kansas], October 2, 1919. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016014/1919-10-02/ed-1/seq-1/.

-

“Ghastly Plot by Blacks Revealed,” The Prescott Daily News [Prescott, Arkansas], October 6, 1919. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90050307/1919-10-06/ed-1/seq-1/.

-

“Bloody Race Riots in Arkansas. Many Whites and Blacks Killed,” The Chicago Whip [Chicago, Illinois], October 11, 1919. https://chroniclingamerica.loc. gov/lccn/sn86056950/1919-10-11/ed-1/seq-8/.

-

Withholding the Truth—Associated Press Abets Mob,” The Monitor [Omaha, Nebraska], October 30, 1919. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/00225879/1919-10-30/ed-1/seq-1/.

-

“Nine People are Killed in Arkansas Race Rioting . . . ,” Richmond Times-Dispatch [Richmond, Virginia], October 2, 1919. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045389/1919-10-02/ed-1/seq-1/.

-

“Joint Resolution to Provide for Annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States (1898),” National Archives and Records Administration, updated February 8, 2022, accessed January 5, 2023. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/joint-resolution-for-annexing-the-hawaiian-islands.

-

“The Illinois house . . . ,” The Oasis [Arizola, Arizona], February 5, 1898. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85032933/1898-02-05/ed-1/seq-4/.

-

“The Hawaiian Rebellion,” Daily Independent [Elko, Nevada], July 12, 1887. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84020355/1887-07-12/ed-1/seq-3/.

-

“Forget Them Not” and “Anti-Annexation,” The Independent [Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii], September 13, 1897. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85047097/1897-09-13/ed-1/seq-2/.

-

"Hawaiian Statehood Due for Vote in House Today or Tomorrow,” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], March 6, 1950. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1950-03-06/ed-1/seq-8/.

-

Robert K. Walsh, “Alaskan-Hawaiian Statehood Appears Doomed This Year,” Evening Star [Washington, D.C.], May 20, 1954. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1954-05-20/ed-1/seq-9/.

-

“President Will Proclaim Hawaii Statehood Friday,” The Nome Nugget [Nome, Alaska], August 19, 1959. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84020662/1959-08-19/ed-1/seq-2/.