W.E.B. Du Bois Papers

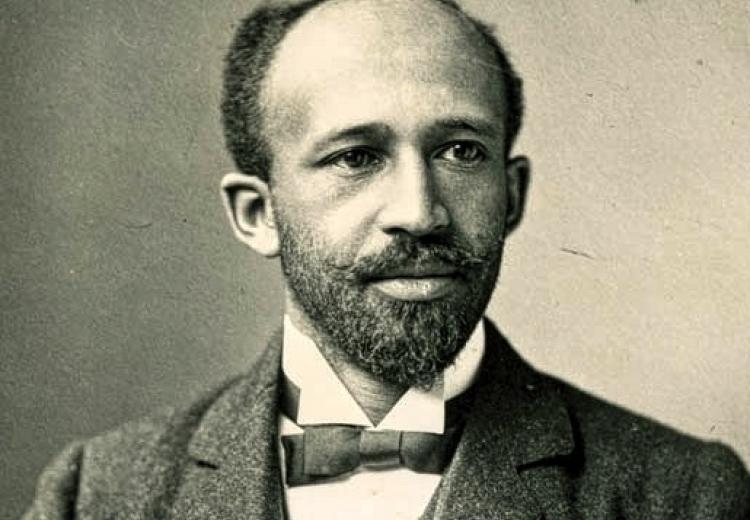

Portrait of W.E.B. DuBois, c. 1907.

The W.E.B. Du Bois papers, containing almost 95,000 items, have been digitized by the University of Massachusetts at Amherst with the support of a grant from the NEH. This ambitious digitization project means that students and scholars around the world have access to the collection to support research, learning, and teaching.

About W.E.B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, born in Massachusetts in 1868, was, among other things, a writer, historian, civil rights activist, and sociologist. He co-founded the NAACP and edited its monthly magazine, The Crisis, which Du Bois used to draw attention to the violent racism faced by Black people in the United States. In addition to writing for the magazine, Du Bois was a prolific author, writing such seminal works as The Souls of Black Folk and Black Reconstruction in America. The former is one of the most important works of sociology addressing the experience of Black people in America. The latter challenged the dominant history of the Reconstruction at the time (written largely by white historians), which ignored the critical role played by Black Americans during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

For Du Bois, race and class were inextricably bound together, and the struggle against race and class inequality was one that transcended national borders. Du Bois supported anti-colonial independence movements in Africa, championed pan-Africanism, and spoke to the importance and power of the "color line" around the world. Recently, historians have begun to contextualize his thought not only in the fight for civil rights in the United States, but as part of a larger movement of anti-imperial thinking among Black intellectuals and activists around the world.

Classroom Connections

This resource is an invaluable source of documents and primary source materials for researching Du Bois's life, The Crisis, the early years of the NAACP, and Du Bois's many influential publications, as well as for understanding the historical and intellectual roots and trajectory of the civil rights movement. It is also a valuable resource for teaching about the international resonances and connections of the U.S. civil rights movement through primary sources.

Students might begin with this letter from Du Bois to Kwame Nkrumah, then prime minister of the Gold Coast (which would become independent Ghana just a month after this letter was written). The following questions and suggestions guide them through a close reading of the document and provide a framework for similar close reading and historical analysis exercises.

Before Reading

- Find some basic biographical information about both Du Bois and Nkrumah. How did they know each other?

- What was happening around the world in February 1957, when this letter was written? What do you know about the wider historical context in both the United States and around the world?

While Reading

- Note pieces of information that you require more context to understand; pieces of information, phrases, or stylistic choices that stand out to you; and anything else to which you'd like to return.

- Read the letter through several times, noting new observations on each reading.

After Reading: Comprehension Questions

- What is Du Bois's vision of "Pan-Africa," as expressed in this letter?

- How does Du Bois describe the condition of imperial control and subsequent independence?

- According to Du Bois, what should differentiate the newly independent nations of Africa from older nations in Europe and the Americas?

After Reading: Further Research

- Refer to the notes you took as you read. What lingering questions do you have that cannot be answered by the letter itself? What sources might you use to answer these questions?

- Look through Du Bois's archive to see if you can find some primary source documents to address your questions. One example is a letter from Du Bois to the Department of State regarding the decision to deny him a passport.

- Du Bois expressed similar ideas in a draft speech from 1956. Examine the digital reproduction of his notes. What can you learn from viewing the original, archival version of the speech that might be missing from other reproductions?