This section provides historical context and framing for EDSITEment’s resources on Latin American and Latino history, as well as ways to integrate NEH-funded projects into the classroom. Lessons are grouped into four thematic and chronological clusters: the indigenous societies of Mesoamerica and the Andes; the colonization of the Americas by Spain; the Mexican Revolution; and immigration and identity in the United States. By no means are these clusters exhaustive; their purpose is to provide context for learning materials available through EDSITEment and NEH-funded projects, and to serve as jumping-off points for further exploration and learning. For each theme, a series of framing questions and activities provides suggestions for connecting and extending the lessons and resources listed for that topic.

Indigenous Mesoamerica and Andes

Indigenous peoples inhabited the Americas long before their “discovery” by Europeans at the end of the fifteenth century. Major civilizations had risen and fallen here, just as they had in Eurasia. One of the most famous archaeological sites in the Americas, Teotihuacan, was home to a complex and wealthy society that collapsed nearly a millennium before Christopher Columbus set out from the Spanish port of Palos in 1492. Students can explore the history and culture of the best-known of the major Mesoamerican civilizations in the lessons The Aztecs: Mighty Warriors of Mexico and Aztecs Find a Home: The Eagle Has Landed. In the South American Andes, the Incas came to control a vast territory crisscrossed with an impressive network of roads traversed by couriers. Students can learn more about the Inca empire and its communication system in Couriers in the Inca Empire: Getting Your Message Across. The NEH-funded project, Mesoamerican Cultures and Their Histories, provides dozens of additional lesson plans about indigenous societies and cultures.

Framing questions and activities:

- Terminology and periodization: Often, names and time periods are taken for granted. These discussion questions prompt students to think critically about the names used to refer to groups of people and to the ways they think about the division of time around the period of European contact with the Americas.

- While we use the term “the Aztecs” most commonly today, this was not what the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan would have called themselves. Historians usually use either Nahuas/Nahua-speaking, to refer to the language these people spoke (and which is still spoken to this day), or Mexica, which refers to the most powerful of the three groups in the Triple Alliance that controlled Tenochtitlan and the Valley of Mexico when Hernán Cortés arrived in 1519. Ask students to reflect on these different names. Why might “Aztec,” which is not what the Mexica specifically or Nahuas generally would have called themselves, have become so common? What is gained from a better understanding of the history of these names and their meanings?

- Ask students to read and explore this timeline of Mesoamerican civilizations. Reflect on the words often used to describe these civilizations and what happened to them after the arrival of Europeans to the New World. What words come to mind? Ask them to reflect on the terms “Pre-Hispanic” and “Pre-Columbian.” What do these terms communicate, and what do they omit? Why do these questions about terminology and periodization matter? Can they think of alternative ways to refer to these time periods? What are the pros and cons of these alternatives?

- Evidence-based claims: The NEH-funded virtual exhibit, Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire, invites students to explore recent archaeological finds made at the site, while placing them in historical and cultural context. As students interact with the site, ask them to create a chart with headings such as “Trade,” “Religion,” “Diet,” “Agriculture,” and “Social Structure,” adapting these categories as you see fit. Students should record what claims the site makes about these different aspects of Teotihuacano society and what evidence is used to support these claims (for example, under “Trade,” a student might write: “Teotihuacan had extensive trading partnerships, evidenced by the prevalence of green quetzal feathers depicted in carvings of elites. These feathers needed to be imported from as far as 600 miles away, indicating that the city was able to command resources from such distances through trade and diplomacy”).

- Holes in the historical record: As students complete the activities in Aztecs Find a Home: The Eagle Has Landed, they will explore another archaeological site: Mexico City itself, which was the seat of Aztec power, the capital of the Spanish colony of New Spain, and now the capital of Mexico. As students observe sites in Mexico City where ruins of Tenochtitlan, colonial structures, and modern skyscrapers are simultaneously visible, ask them to reflect on the other kinds of evidence an historian might use to learn about the Aztecs. Though Nahuatl was a written language, many Nahua texts were destroyed during conquest and subsequent attempts to convert indigenous people to Catholicism. Surviving texts produced in Nahuatl and by indigenous authors were almost all created after the conquest. What does this mean for historians and students? How might they approach what sources do exist? Students can reflect on these questions independently and share their thoughts with a partner, small group, or whole class. For grades 11-12, this exercise would be a good segue into some of the materials from The Conquest of Mexico, a lesson plan created by Dr. Nancy Fitch for the American Historical Association.

- Comparing and contrasting: After students have learned about both the Aztec and Inca empires using the EDSITEment lesson plans Aztecs Find a Home: The Eagle Has Landed, The Aztecs: Mighty Warriors of Mexico, and Couriers in the Inca Empire: Getting Your Message Across, ask them to compare and contrast important features of these two civilizations. How were these societies organized? How did tribute and taxation work in each? Language? What territories did each control, and by what mechanisms? Students can work in groups to research different points of comparison before sharing their findings and reflecting as a class.

Contact, Conquest, Colonization

When Spanish conquistadors reached the New World, they encountered these complex indigenous societies with their sophisticated, surplus-producing economies, as well as smaller, nomadic societies. The early Spanish colonizers, far fewer in number than the populous New World civilizations they sought to conquer, often attempted to graft onto existing tribute systems to extract this surplus wealth, with major indigenous cities like Tenochtitlan (situated where Mexico’s capital city is to this day) serving as the geographic loci of early colonization. Spanish colonization was helped along by Spain’s military technology, alliances with rival indigenous groups, and, most crucially, disease. The Spaniards introduced contagious diseases, such as smallpox, to which indigenous people had little immune resistance. Indigenous populations were decimated by the combination of warfare, disease, and harsh labor on Spanish plantations. As Spain’s empire expanded, the Spanish crown depended heavily on the Catholic Church to subjugate indigenous peoples, both settled and nomadic, and integrate them into the colonial economy. Along New Spain’s northern frontier, which stretched into the present-day United States and where contact and conflict with other burgeoning European empires was likely, fortified missions relying on coerced indigenous settlement and labor were important institutions for expanding the geographic and demographic reach of the Spanish empire. In the EDSITEment lesson plan, Mission Nuestra Señora de la Concepción and the Spanish Mission in the New World, students are invited to use the image of the mission to explore one instance of the missionary institution in the mid-17th century. This lesson might be further enriched with an exploration of Spanish mission sites in California in The Road to Santa Fe: A Virtual Excursion.

The processes of conquest and colonization were often carefully documented by Spaniards, creating a rich—and problematic—historical and literary record. A prime example, the journey of Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, can be found by visiting New Perspectives on the West. For another perspective on Spanish exploration and settlement, visit Web de Anza, which is packed with primary source documents and multimedia resources covering Juan Bautista de Anza's two overland expeditions that led to the colonization of San Francisco in 1776. Surviving indigenous perspectives are more difficult to find. Even when available, these sources pose significant interpretive challenges because they were often mediated through Spanish individuals or institutions. For grades 11-12, The Conquest of Mexico provides a plethora of primary and secondary sources (including texts produced by indigenous people), lesson plans, and exercises in historical analysis. Finally, Southwest Crossroads offers lesson plans, in-depth articles, and hundreds of digitized primary sources that explore the many narratives people have used to make sense of this region, from colonization to the present.

Framing questions and activities:

- Source interpretation: In several EDSITEment lessons about Spanish colonization, students are asked to analyze images to glean information about colonial institutions and practices. They have also confronted the problem of authorship and perspective in primary sources from this period, with the archive of the colonizer serving as the main paradigm through which the processes of conquest and colonization are understood. Two lessons from the NEH-funded website, Southwest Crossroads: Cultures and Histories of the American Southwest, throw this problem into sharp relief. In Encounters—Hopi and Spanish Worldviews, students work with texts written by both Hopi and Spanish authors, as well as maps and images, to learn about missionaries’ violent attempts to convert Hopi villagers to Catholicism and to reflect on the lasting impacts of those attempts for Hopi culture and society. In Invasions—Then and Now, students work with a Spanish account of a sixteenth-century expedition, a map of similar expeditions, and a twentieth-century poem to reflect on the echoes and reverberations of the colonial past.

- Image analysis: The EDSITEment lesson Mission Nuestra Señora de la Concepción and the Spanish Mission in the New World is based on the analysis of a watercolor painting of the mission. Students can learn more about the architecture of Spanish missions from the National Park Service, and use their insights to analyze the architecture of other missions pictured in the University of California’s digital exhibition of Spanish mission sites in California. They can explore additional photographs of Spanish missions, as well as get a sense for the distribution of missions in what is now the United States, from Designing America, a website created by the Fundación Consejo España-Estados Unidos and the National Library of Spain. Ask students to think critically about this last source in particular as they read through its descriptions of mission architecture and function. How does this information compare with, for example, this Hopi author’s account of the construction of a Spanish mission? Why might this be?

The Mexican Revolution

Beginning in 1910 and continuing for a decade, the Mexican Revolution had profound ramifications for both Mexican and U.S. history. The EDSITEment Closer Readings Commentary on the Mexican Revolution provides background on the conflict and its cultural, artistic, and musical legacies. A lesson plan for the Mexican Revolution covers the context for, unfolding of, and legacies of the Revolution for later social movements. Students can learn about the role played by the United States in the Mexican Revolution in the EDSITEment lesson plan “To Elect Good Men”: Woodrow Wilson and Latin America.

Framing questions and activities:

- Guided research: Ask students to explore the Mexican Revolution in greater detail. Useful sources, in addition to those already mentioned, include:

The following questions and prompts can guide their research:

- Describe Mexican political, economic, and social conditions during the Porfiriato.

- What were some of the causes of the Mexican Revolution?

- Who were some of the major military actors in the Mexican Revolution? Why were they involved, and what were they fighting for?

- How have different people experienced and understood the Mexican Revolution? Provide at least two different individuals’ perspectives.

Before students begin their research, ask them to review the sources provided and give examples of primary and secondary sources. As they answer the guiding questions, they should use at least one primary and one secondary source to support each of their answers.

- Comparing and contrasting: After studying the Mexican Revolution and U.S. involvement in it, ask students to make comparisons with another revolution or conflict that they have studied. They might consider the following factors:

- Major divisions and conflicts

- The role of foreign intervention

- Outcomes of the conflicts

- Major actors involved in the conflict

- The way the conflict was represented in contemporary accounts (for example, by researching coverage in historic newspapers on Chronicling America)

- Ways the conflict is commemorated today

Students should create presentations of their findings to present to each other. As they listen to their classmates, ask students to take notes about the various revolutions. Use their observations to start a discussion about the word “revolution.” What should be classified as a revolution? Could a coup be a revolution? A civil war? Why do they think some civil wars are classified as such, while others are labeled revolutions, even though the impacts of both might be equally profound?

Immigration and Identity in the United States

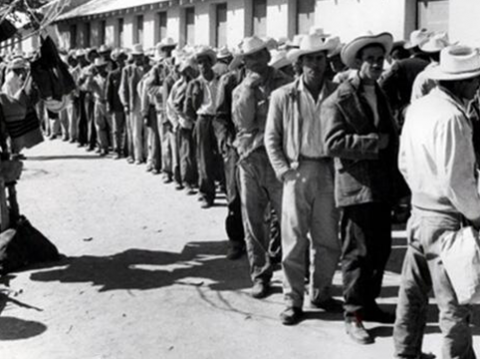

The border between the United States and Mexico has changed over time, and much of the territory that now forms the southwestern United States was at one point Mexican. But the movement of people, goods, money, and ideas has always been a feature of this border. That movement, especially of people, has not always been voluntary. During the Great Depression, many thousands—and by some estimates as many as two million—Mexicans were forcibly deported from the United States. Over half of those deported were U.S. citizens.

Less than a decade later, U.S. policy changed completely: rather than deporting Mexican-Americans and Mexicans, the United States was desperate to draw Mexican laborers into the country to ease agricultural labor shortages caused by World War II. As a result, the Mexican and U.S. governments established the Bracero Program, which allowed U.S. employers to hire Mexican laborers and guaranteed those laborers a minimum wage, housing, and other necessities. However, braceros’ wages remained low, they had almost no labor rights, and they often faced violent discrimination, including lynching. Oral histories from braceros, as well as several lesson plans about the program, can be found at the NEH-funded Bracero History Archive

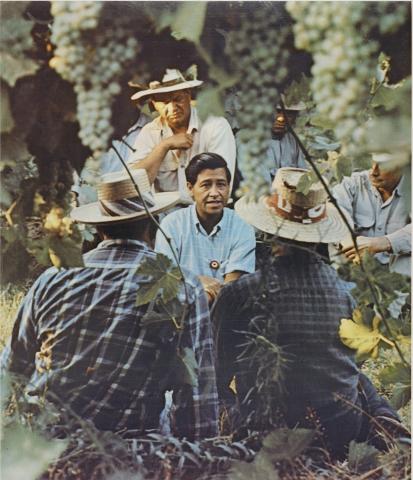

The Bracero program ended in 1964. Two years before, in 1962, César Chávez had co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) with Dolores Huerta. The NFWA would later become the United Farm Workers (UFW). In response to the low wages and terrible working conditions experienced by farmworkers, Chávez and Huerta organized migrant farmworkers to press for higher wages, better working conditions, and labor rights. Students can learn more about Chávez and Huerta in the EDSITEment lesson "Sí, se puede!": Chávez, Huerta, and the UFW.

The UFW was part of the larger civil rights movement of the 1960s and beyond. The Chicano movement fought for the rights of Mexican-Americans and against anti-Mexican racism and discrimination. It was also important in the creation of a new collective identity for, and sense of solidarity among, Mexican-Americans. Other ethnic categories sought to include a greater number of people of Latin American heritage and to capture aspects of their shared experience in the United States. In the 1970s, activists pushed for the inclusion of “Hispanic” on the U.S. Census in order to disaggregate poverty rates among Latinos and whites. Since then, different terms have emerged to describe this diverse population, including Latino and Latinx. The PBS project Latino Americans (available in English and Spanish) documents the experiences of Latinos in the United States and includes a selection of lesson plans for grades 7-12, as well as shorter, adaptable classroom activities. Additional resources for teaching immigration history include the Closer Readings Commentary “Everything Your Students Need to Know About Immigration History,” which provides an overview of immigration history in the United States, and Becoming US, a collection of teaching resources on migration and immigration created by the Smithsonian Institution.

Framing questions and activities:

- Terminology and identity: There are many words to describe the experiences and identities of Latinos in the United States. The words “Hispanic” and “Latino” are intentionally broad and meant to capture a wide diversity of identities and experiences, which means that they can also erase or diminish specific individuals and their stories. Teaching Tolerance has created and compiled a selection of educational materials, including readings, discussion questions, and suggestions for teachers, to help address this topic in the classroom. Within this Teacher’s Guide, the lessons in the section “Borderlands: Lessons from the Chihuahuan Desert” address questions of identity, belonging, and difference in greater depth.

- Comparing and contrasting: Like "Sí, se puede!": Chávez, Huerta, and the UFW, the EDSITEment lesson Martin Luther King, Jr., Gandhi, and the Power of Nonviolence addresses the civil rights movement and the use of nonviolent protest to fight racism, discrimination, and exploitation. Ask students to research a specific protest organized by the UFW and one by leaders of the movement for African American civil rights. They might return to the lessons for some ideas, or work on a protest not included in the lesson plans. Ask them to discuss the following questions with respect to their chosen protests:

- What actors were involved? What united them?

- What were they protesting?

- What strategies did they use? Describe the mechanics of the protest: its location and duration, what actions the protesters took, how they responded to any resistance or confrontations, how and why the protest ended. Depending on the protest they have chosen, a timeline and/or map may be a good way to represent this information.

- Were there any divisions, controversies, or conflicts within the movement?

- What responses met the protest? How was the protest represented in different media outlets from the time?

- How has the protest been commemorated or remembered since it took place? How have those commemorations changed over time?

- If you were to design a monument, event, or other public commemoration of this protest, what would you create? Why?

- Guided research: To expand students’ understanding of protest and resistance in the United States, ask them to research a contemporary protest movement. They might use the questions from the “Comparing and contrasting” activity, above, as guidance. Students should create presentations about their chosen movement to share their findings with the class; afterwards, they can discuss any similarities and differences they noticed between the contemporary protests, as well as continuities with and changes from the historical protests they have studied in class.