Everything Your Students Need to Know About Immigration History

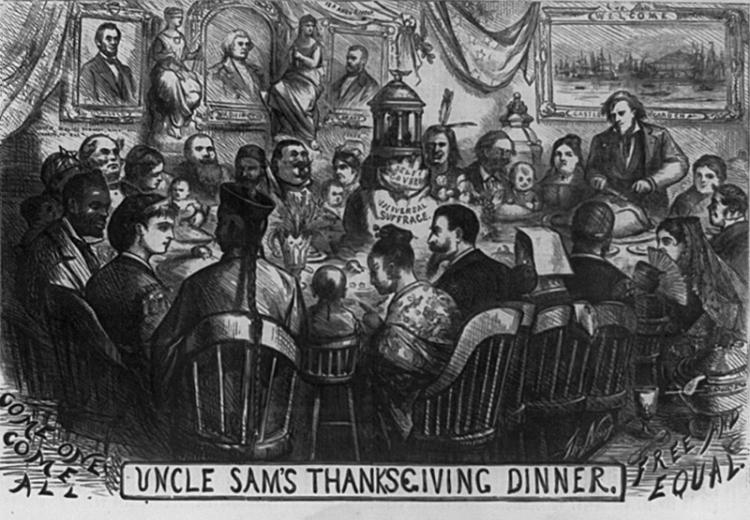

“Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner,” by Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly (20 November 1869)

Madeline Hsu, PhD, University of Texas at Austin

In 1869, Thomas Nast, the German immigrant cartoonist, envisioned Uncle Sam hosting a diverse array of guests at his Thanksgiving table, including Germans, French, Spaniards, Native Americans, Irish, and a range of other Europeans amicably sharing food and conversation with each other. Columbia, who for Nast symbolized U.S. democratic ideals, sits opposite to Uncle Sam chatting amiably with a Chinese and African American man at either side. In the window after the Civil War ended slavery, and before the United States began systematically restricting immigration in the late nineteenth century, Nast festooned this pleasant, multiracial family gathering with the idealistic slogans “universal suffrage,” “come one come all,” and “free and equal.”

That same year, the famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass also celebrated the absorptive, inclusive capacities of the American nation and economy. In the speech, “Our Composite Nationality,” he criticized an 1862 law targeting Chinese for immigration restriction by asserting the “eternal, universal and indestructible” human rights “of migration; the right which belongs to no particular race, but belongs alike to all and to all alike.” Douglass reassured his listeners that a great nation such as the United States could provide a home and brighter futures to all manner of men, and that there was no need to try to exclude any persons.

Within a few years, however, this vision of a harmonious, multiracial, multicultural America had receded under the onslaught of economic recession, divisive racial politics, the centralization of wealth with industrialization, and labor unrest. Incendiary nativist campaigns called on the federal government to limit immigration as a solution to the nation’s problems, and began by targeting Chinese as racially inassimilable, along with the poor, criminals, and the insane as drains on public resources. These dark conditions produced the United States’ earliest experiments in immigration restriction, which involved the identifying of particular groups considered so undesirable that they merited exclusion. Once Congress started passing laws restricting immigration to some people, but not others, the U.S. government also quickly realized that enforcing immigration laws required it to develop bureaucracies and strategies for ways to distinguish between legal and illegal entries, document and keep records of identities and entries, and police crossings across the U.S.’s extensive land and maritime borders.

The first systematically enforced immigration laws were passed in 1882 and since then, Congress has identified an expanding array of targets, including the most restrictive laws in 1924 that imposed absolute numeric caps on annual immigration. The executive branch has claimed tremendous powers to enforce these laws, with a consequent diminishing of the legal rights and protections for unauthorized immigrants, all of which has been deemed constitutional by the Supreme Court. Nonetheless, the United States remains riven and seemingly irreconcilable about what role immigrants and immigration play in our national interests, and what kinds of priorities and ideals we should pursue in restricting immigration.

Teach Immigration History was created for high school teachers of U.S. history and civics, as well as for a general audience, to explain this important and complicated history, by the Immigration and Ethnic History Society with support from The University of Texas at Austin. The backbone of the website is an 80-item chronology of key events, laws, and court rulings that are further explained by a dozen thematic lesson plans on topics such as citizenship, an overview of major laws, gender and immigration, and migration within the Americas. Each lesson plan provides a discussion, teaching exercises and assessment mechanism, and primary sources. A glossary explains key terms and concepts and the website suggests additional resources. With this teaching resource, you will be better able to improve your students’ understanding of U.S. immigration history so that they will be able to make more sense of the important debates and choices that have and will continue to shape our immigration system.

About the Author: Dr. Madeline Y. Hsu is president of the Immigration and Ethnic History Society and vice-president of the International Society for the Study of Chinese Overseas. She is Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin and served as Director of the Center for Asian American Studies there from 2006 until 2014. She received her undergraduate degrees in History from Pomona College and PhD from Yale University. Her first book was Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration between the United States and South China, 1882-1943 (Stanford University Press, 2000). Her most recent monograph, The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority (Princeton University Press, 2015), received awards from the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations, the Immigration and Ethnic History Society, the Asian Pacific American Librarians Association, and the Association for Asian American Studies. Her third book, Asian American History: A Very Short Introduction was published by Oxford University Press in 2016 and she co-edited the anthology, A Nation of Immigrants Reconsidered: U.S. Society in an Age of Restriction, 1924-1965 (UIP 2019) with Maddalena Marinari and Maria Cristina Garcia.

Teach Immigration History was developed by the following team of scholars and curriculum designers: Madeline Hsu (University of Texas-Austin), Esther J. Kim (University of Texas-Austin), Joanna Batt (University of Texas-Austin), Charlie Fanning (University of Maryland), Adam Goodman (University of California-Irvine), Jennifer Graber (University of Texas-Austin), Marilynn Johnson (Boston College), Rosina Lozano (Princeton University), Gráinne McEvoy, Sarah McNamara (Texas A&M University), Lucy Salyer (University of New Hampshire), Neil Shanks (Baylor University), Ruth Wasem (University of Texas-Austin), and K. Scott Wong (Williams College). The Web Development team includes: Stacy Vlasits, Suloni Robertson, Rodrigo Villarreal, Jaclyn Alford, and Kathy Vong.